- Winscp Ssh Key

- Winscp Connect To Openssh Server

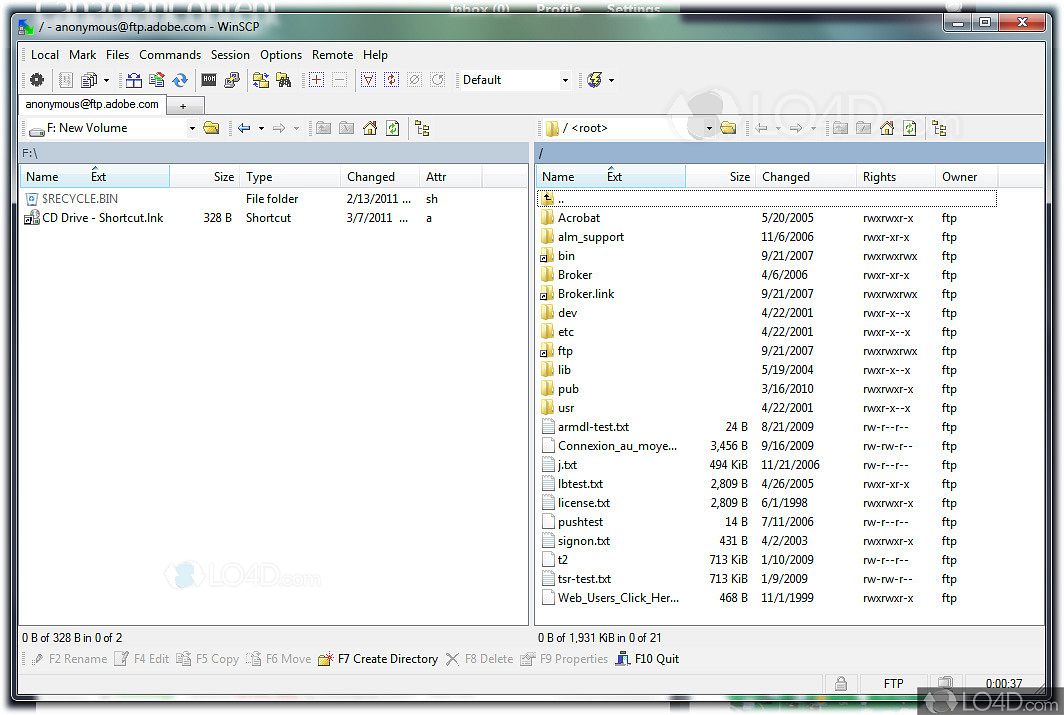

- Scp For Windows

- Winscp Openssh Version

- Winscp Openssh Windows

- Ssh Transfer File

- Winscp Openssh Key

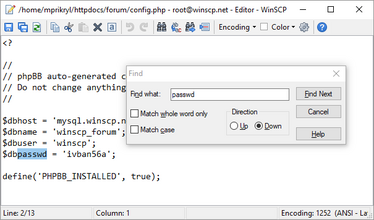

WinSCP is open source and does not come with any support. Many organizations have massive amounts of SSH keys that must be properly managed. If left unmanaged, they pose a major risk and compliance issue. SSH tunneling, unless properly controlled, can allow backdoor access from the Internet into internal networks. OpenSSH legacy support. OpenSSH implements all of the cryptographic algorithms needed for compatibility with standards-compliant SSH implementations, but since some of the older algorithms have been found to be weak, not all of them are enabled by default.

SSH is ubiquitous. It’s the de-facto solution for remote administration of *nix systems. But SSH has some pretty gnarly issues when it comes to usability, operability, and security.

You’re probably familiar with these issues:

- SSH user experience is terrible. SSH user on-boarding is slow and manual. Connecting to new hosts produces confusing security warnings. You’re left with weird new credentials to manage with little guidance on how to do so.

- Operating SSH at scale is a disaster. Key approval & distribution is a silly waste of time. Host names can’t be reused. Homegrown tools scatter key material across your fleet that must be cleaned up later to off-board users.

- SSH encourages bad security practices. Rekeying is hard, so it’s not done. Users are exposed to key material and encouraged to reuse keys across devices. Keys are trusted permanently, so mistakes are fail-open.

The good news is this is all easy to fix.

None of these issues are actually inherent to SSH. They’re actually problems with SSH public key authentication. The solution is to switch to certificate authentication.

SSH certificate authentication makes SSH easier to use, easier to operate, and more secure.

Background

At smallstep, certificates are kind of our jam. We build open source software that lets you run your own private certificate authority and manage X.509 (TLS/HTTPS) certificates.

SSH certificates have been on our radar for a while. From our perspective they’re all pros, no cons. But no one uses them. Why not? We’ve asked hundreds of people that question. Here’s what we found out:

- People do use SSH certificates. In fact, pretty much everyone operating at scale that knows what they’re doing does (Facebook, Uber, Google, Netflix, Intercom, Lyft, etc), but…

- Certificates and public key infrastructure (PKI) are hard to grok. People don’t immediately understand the benefits.

- There’s a (small) tooling gap that exacerbates this knowledge gap. It’s not hard to fill, but people are wary to do so themselves without a deeper understanding of PKI concepts.

- More than anything, SSH certificates haven’t gotten the press they deserve. Most people we asked hadn’t heard of them at all.

We’re convinced that SSH certificates are the right way to do SSH. They’re not that hard to understand, and it’s well worth the effort. SSH certificates deserve more press, and broader use.

Public key authentication

Most SSH deployments use public key authentication, which uses asymmetric (public key) cryptography with a public / private key pair generated for each user & host to authenticate.

The magic of asymmetric cryptography is the special correspondence between a public and private key. You can sign data with your private key and someone else can verify your signature with the corresponding public key. Like a hash, it’s computationally infeasible to forge a signature. Thus, if you can verify a signature, and you know who owns the private key, you know who generated the signature.

Simple authentication can be implemented by challenging someone to sign a big random number. If I open a socket to you and send a random number, and you respond with a valid signature over that number, I must be talking to you.

This is an oversimplification, but it’s more or less how SSH public key authentication works. Certificate authentication works the same way, but with an important twist that we’ll get to in a moment.

To SSH to a host using public key authentication the host needs to know your public key. By default, your public key must be added to ~/.ssh/authorized_keys. Maintaining this file for every user across a fleet is operationally challenging and error prone.

SSH user onboarding with public key authentication usually starts with some baroque incantation of ssh-keygen, hopefully pulled from a runbook, but more likely cribbed from stack overflow. Next you’ll be asked to submit your public key for approval and distribution. This process is typically manual and opaque. You might be asked to email an administrator or open a JIRA ticket. Then you wait. While you’re doing that, some poor operator gets interrupted and told to add your key to a manifest in some repo and trigger a deploy. Once that’s done you can SSH. Since key bindings are permanent, your SSH access will continue in perpetuity until someone reverses this process.

Certificate authentication

Certificate authentication eliminates key approval and distribution. Instead of scattering public keys across static files, you bind a public key to a name with a certificate. A certificate is just a data structure that includes a public key, name, and ancillary data like an expiration date and permissions. The data structure is signed by a certificate authority (CA).

To enable certificate authentication simply configure clients and hosts to trust any certificates signed by your CA’s public key.

On each host, edit /etc/ssh/sshd_config, specifying the CA public key for verifying user certificates, the host’s private key, and the host’s certificate:

On each client, add a line to ~/.ssh/known_hosts specifying the CA public key for verifying host certificates:

That’s it. That’s literally all that you need to do to start using certificate authentication. You can even use it alongside public key authentication to make transitioning easier.

Static keys in ~/.ssh/authorized_keys are no longer needed. Instead, peers learn one another’s public keys on demand, when connections are established, by exchanging certificates. Once certificates have been exchanged the protocol proceeds as it would with public key authentication.

Certificate authentication improves usability

With public key authentication, when you SSH to a remote host for the first time, you’ll be presented with a security warning like this:

You’ve probably seen this before. If you’re like most people, you’ve been trained to ignore it by just typing “yes”. That’s a problem because this is a legitimate security threat. It’s also a pretty horrendous user experience. I’d wager the vast majority of SSH users don’t actually understand this warning.

When you SSH to a host, the host authenticates you. Your SSH client also attempts to authenticate the host. To do so your client needs to know the host’s public key. Host public keys are stored in a simple database in ~/.ssh/known_hosts. If your client can’t find the host’s public key in this database you get this warning. It’s telling you that the host can’t be authenticated!

What you’re supposed to do is verify the key fingerprint out-of-band by asking an administrator or consulting a database or something. But no one does that. When you type “yes” the connection proceeds without authentication and the public key is permanently added to ~/.ssh/known_hosts. This is the trust on first use (TOFU) anti-pattern.

Since certificate authentication uses certificates to communicate public key bindings, clients are always able to authenticate, even if it’s the first time connecting to a host. TOFU warnings go away.

Certificate authentication also offers a convenient place to gate SSH with custom authentication: when the certificate is issued. This can be leveraged to further enhance SSH usability. In particular, it let’s you extend single sign-on (SSO) to SSH. SSO for SSH is certificate authentication’s biggest party trick. We’ll return to this idea and see how it further enhances usability and security later. For now, let’s move on to operability.

Certificate authentication improves operability

Eliminating key approval and distribution has immediate operational benefits. You’re no longer wasting ops cycles on mundane key management tasks, and you eliminate any ongoing costs associated with monitoring and maintaining homegrown machinery for adding, removing, synchronizing, and auditing static public key files across your fleet. Victoria 2 westernize cheat.

The ability to issue SSH user certificates via a variety of authentication mechanisms also facilitates operational automation. If a cron job or script needs SSH access it can obtain an ephemeral SSH certificate automatically, when it’s needed, instead of being pre-provisioned with a long-lived, static private key.

SSH public key authentication introduces some weird operational constraints around host names that certificate authentication eliminates. As we’ve seen, when an SSH client connects to a host for the first time it displays a TOFU warning to the user. When the user types “yes” the host’s public key is added locally to ~/.ssh/known_hosts. This binding between the host name and a specific public key is permanent. If the host presents a different public key later, the user gets an even scarier host key verification failure error message that looks like this:

This makes it operationally challenging to reuse host names. If prod01.example.com has a hardware failure, and it’s replaced with a new host using the same name, host key verification failures will ensue. This usually results in a bunch engineers contacting secops to tell them they’re being hacked.

Ignoring host key verification failures has the exact same attack surface area as not knowing the key at all. Curiously, OpenSSH chooses to soft-fail with an easily bypassed prompt when the key isn’t known (TOFU), but hard-fails with a much scarier and harder to bypass error when there’s a mismatch.

In any case, certificates fix all of this since a current name-to-public-key binding is communicated when a connection is established. Changing the host’s public key is fine, as long as the host also gets a new certificate. You can safely reuse host names and even run multiple hosts with the same name. You’ll never see a host key verification failure again. Beyond name reuse, we’ll soon see that eliminating host key verification failures is one of the many ways certificate authentication facilitates good security hygiene.

Certificate authentication improves security

While the SSH protocol itself is secure, public key authentication encourages a bunch of bad security practices and makes good security hygiene hard to achieve.

With public key authentication, keys are trusted permanently. A compromised private key or illegitimate key binding may go unnoticed or unreported for a long time. Key management oversight (e.g., forgetting to remove an ex-employee’s public keys from hosts) results in SSH failing open: unauthorized access without end.

Certificates, on the other hand, expire. In an incident — a mistake, theft, misuse, or key exfiltration of any form — compromised SSH credentials will expire automatically, without intervention, even if the incident goes unnoticed or unreported. SSH certificates are fail-secure. Access expires naturally if no action is taken to extend it. And when SSH users and hosts check in periodically with your CA to renew their credentials, a complete audit record is produced as a byproduct.

We’ve already seen how public key authentication trains users to ignore serious security warnings (TOFU) and triggers spurious security errors. This is more than an operational nuisance. Confusion caused by host key verification failure discourages host rekeying (i.e., replacing a host’s key pair). Host private keys aren’t very well protected, so periodic rekeying is good practice. Rekeying may be required after a breach or after offboarding a user. But, to avoid disruption from ensuing host key verification failures, it’s often not done. Certificate authentication makes rekeying hosts trivial.

Public key authentication also makes rekeying difficult for users. Key approval and distribution is annoying enough that users are reluctant to rekey, even if you’ve built tools to make it possible. Worse, frustrated users copy private keys and reuse them across devices, often for many years. Key reuse is a serious security sin. Private keys are never supposed to be transferred across a network. But SSH public key authentication exposes users directly to sensitive private keys, then fails to give them usable tools for key management. It’s a recipe for misuse and abuse.

An SSH CA, coupled with a simple command-line client for users, can streamline key generation and insulate users from a lot of unnecessary detail. Certificate authentication can’t completely eliminate all security risks, but it does facilitate SSH workflows that are more intuitive, easier to use, and harder to misuse.

An ideal SSH flow

SSH certificate authentication is the foundation of what I think is the ideal SSH flow.

To SSH, users first run a login command in their terminal (e.g., step ssh login):

A browser is opened and an SSO flow is initiated at your organization’s identity provider:

A web-based SSO flow makes it easy to leverage strong MFA (e.g., FIDO U2F) and any other advanced authentication capabilities your identity provider offers. Users login with a familiar flow, and removing a user from your canonical identity provider ensures prompt termination of SSH access.

Once the user completes SSO, a bearer token (e.g., an OIDC identity token) is returned to the login utility. The utility generates a new key pair and requests a signed certificate from the CA, using the bearer token to authenticate and authorize the certificate request.

The CA returns a certificate with an expiry long enough for a work day (e.g., 16-20 hours). The login utility automatically adds the signed certificate and corresponding private key to the user’s ssh-agent.

Users needn’t be aware of any of this detail. All they need to know is that, in order to use SSH, they must first run step ssh login. Once that’s done they can use SSH like normal:

Like browser cookies, short-lived certificates issued by this flow are ephemeral credentials, lasting just long enough for one work day. Like logging into a website, logging into SSH creates a session. It’s a simple process that must be completed, at most, once per day. This is infrequent enough that strong MFA can be used without frustrating or desensitizing users.

New private keys and certificates are generated automatically every time the user logs in, and they never touch disk. Inserting directly into ssh-agent insulates users from sensitive credentials. If a user wants to connect from a different device it’s easier for them to run step ssh login there than it is to exfiltrate keys from ssh-agent and reuse them.

There are lots of possible variations of this flow. You can adjust the certificate expiry, use PAM authentication at the CA instead of SSO, generate the private key on a smart card or TPM, opt not to use ssh-agent, or move MFA to the actual SSH connection. Personally, I think this combination offers the best balance of security and usability. Indeed, relative to most existing SSH deployments it’s operationally simpler, more secure, and more usable.

Critics of SSH certificate authentication say that it’s new, not well supported, and the tooling doesn’t exist to use certificates in practice. The truth is, certificate authentication was added inOpenSSH 5.4almost a decade ago. It’s battle tested and used in production by massive operations. And the tooling required to build this ideal SSH flow is available today.

Tools

There are lots of existing tools for managing SSH certificates. Here are a few:

ssh-keygencan generate root certificates and sign user & host certificatesnetflix/blessis Netflix’s SSH CA that runs in AWS Lambda and uses IAMnsheridan/cashieris Intercom’s SSH CAuber/pam-usshlets you use certificates to authorizesudousehashicorp/vaulthas an SSH secrets engine

For our part, the most recent release of step & step-ca (v0.12.0) adds basic SSH certificate support. In other words:

step-cais now an SSH CA (in addition to being an X.509 CA)stepmakes it easy for users and hosts to get certificates fromstep-ca

SSH workflows aren’t fully fleshed out yet, but these tools already do everything you need for the ideal flow.

With the appropriate configuration of step-ca you can use step to:

Get a host certificate automatically at startup

To demonstrate, let’s create a new EC2 instance with the aws CLI tool. The interesting bits are tucked in some light configuration (using a user-data startup script) that gets a host certificate and enables certificate authentication for users:

Note: you should be able to use our instance identity document support here, but we’ve got a few kinks to work out. Stay tuned.

Get a user certificate using SSO (OAuth OIDC)

Now we’ll use step ssh certificate locally (you can brew install step) to generate a new key pair, get a certificate from the CA using SSO, and automatically add the certificate and private key to ssh-agent.

That sounds like a lot, but it’s just one command:

Once that’s done we can SSH to the instance we just created, using certificate authentication, with no TOFU!

For more info check out our getting started guide and SSH example repo. Make sure you pass the --ssh flag to step ca init when you’re setting up the CA (the getting started guide doesn’t do this).

There’s a lot more that can be done to make SSH certificate authentication even more awesome. We’re working on that. If you have any ideas, let us know!

Use SSH certificates

SSH certificate authentication does a lot to improve SSH. It eliminates spurious TOFU warnings and host key verification failures. It lets you drop complex key approval & distribution processes and extend SSO to SSH. It makes rekeying possible for hosts and easier than key reuse for users. It makes SSH keys ephemeral, making key management oversights fail-secure.

You can deploy an SSH CA and reconfigure hosts in a matter of minutes. It’s easy to transition — you can continue supporting public key authentication at the same time.

SSH certificate authentication is the right way to do SSH.

At smallstep, we’re looking forward to improving our SSH story. We’re building out infrastructure and streamlined workflows to make SSH better for everyone. And keep an eye on our blog because we have a lot more to say about SSH!

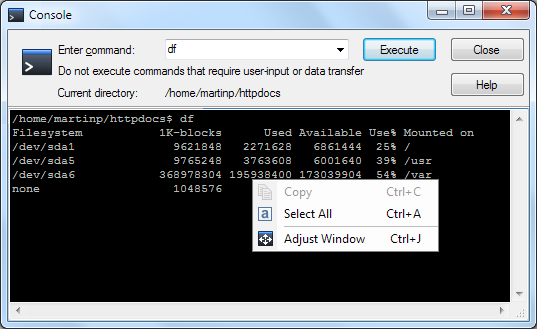

SSH tunneling (also referred to as SSH port forwarding) is simply routing the local network traffic through SSH to remote hosts. This implies that all your connections are secured using encryption. It provides an easy way of setting up a basic VPN (Virtual Private Network), useful for connecting to private networks over unsecure public networks like the Internet.

You may also be used to expose local servers behind NATs and firewalls to the Internet over secure tunnels, as implemented in ngrok.

SSH sessions permit tunneling network connections by default and there are three types of SSH port forwarding: local, remote and dynamic port forwarding.

In this article, we will demonstrate how to quickly and easily set up SSH tunneling or the different types of port forwarding in Linux.

Testing Environment:

For the purpose of this article, we are using the following setup:

- Local Host: 192.168.43.31

- Remote Host: Linode CentOS 7 VPS with hostname server1.example.com.

Usually, you can securely connect to a remote server using SSH as follows. In this example, I have configured passwordless SSH login between my local and remote hosts, so it has not asked for user admin’s password.

Local SSH Port Forwarding

This type of port forwarding lets you connect from your local computer to a remote server. Assuming you are behind a restrictive firewall or blocked by an outgoing firewall from accessing an application running on port 3000 on your remote server.

You can forward a local port (e.g 8080) which you can then use to access the application locally as follows. The -L flag defines the port forwarded to the remote host and remote port.

Winscp Ssh Key

Adding the -N flag means do not execute a remote command, you will not get a shell in this case.

The -f switch instructs ssh to run in the background.

Now, on your local machine, open a browser, instead of accessing the remote application using the address server1.example.com:3000, you can simply use localhost:8080 or 192.168.43.31:8080, as shown in the screenshot below.

Remote SSH Port Forwarding

Remote port forwarding allows you to connect from your remote machine to the local computer. By default, SSH does not permit remote port forwarding. You can enable this using the GatewayPorts directive in you SSHD main configuration file /etc/ssh/sshd_config on the remote host.

Open the file for editing using your favorite command line editor.

Winscp Connect To Openssh Server

Look for the required directive, uncomment it and set its value to yes, as shown in the screenshot.

Save the changes and exit. Next, you need to restart sshd to apply the recent change you made.

Scp For Windows

Next run the following command to forward port 5000 on the remote machine to port 3000 on the local machine.

Once you understand this method of tunneling, you can easily and securely expose a local development server, especially behind NATs and firewalls to the Internet over secure tunnels. Tunnels such as Ngrok, pagekite, localtunnel and many others work in a similar way.

Winscp Openssh Version

Dynamic SSH Port Forwarding

This is the third type of port forwarding. Unlike local and remote port forwarding which allow communication with a single port, it makes possible, a full range of TCP communications across a range of ports. Dynamic port forwarding sets up your machine as a SOCKS proxy server which listens on port 1080, by default.

For starters, SOCKS is an Internet protocol that defines how a client can connect to a server via a proxy server (SSH in this case). You can enable dynamic port forwarding using the -D option.

The following command will start a SOCKS proxy on port 1080 allowing you to connect to the remote host.

Winscp Openssh Windows

From now on, you can make applications on your machine use this SSH proxy server by editing their settings and configuring them to use it, to connect to your remote server. Note that the SOCKS proxy will stop working after you close your SSH session.

Read Also: 5 Ways to Keep Remote SSH Sessions Running After Closing SSH

Summary

Ssh Transfer File

In this article, we explained the various types of port forwarding from one machine to another, for tunneling traffic through the secure SSH connection. This is one of the very many uses of SSH. You can add your voice to this guide via the feedback form below.

Winscp Openssh Key

Attention: SSH port forwarding has some considerable disadvantages, it can be abused: it can be used to by-pass network monitoring and traffic filtering programs (or firewalls). Attackers can use it for malicious activities. In our next article, we will show how to disable SSH local port forwarding. Stay connected!